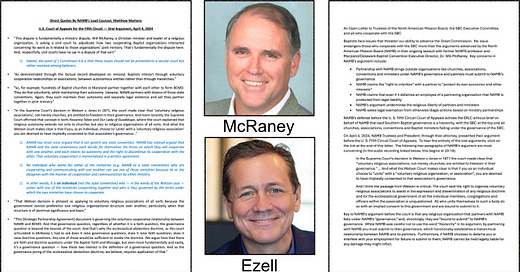

‘Helpful Information’ about McRaney-NAMB case offered by Ezell to association leaders after open letter is sent to NAMB and SBC Executive Committee trustees

Kevin Ezell, president of the North American Mission Board (NAMB) of the Southern Baptist Convention, broke years of refusing public comment May 10 in an email to state Baptist association leaders providing what he says is “helpful information” in the ongoing defamation case involving NAMB and former state executive director Will McRaney. The email came shortly after an open letter was sent to NAMB and the SBC Executive Committee by current and former SBC leaders disputing NAMB’s claims in the case.

“Just like you, we are focused on our mission and high priority items right now, but it’s that time of year when misinformation flourishes on social media. In case you are asked about it, I have attached a brief summary of recent court proceedings involving our case,” Ezell said in an email.

“It’s very clear and uses direct quotes from what our attorney actually said in court. As always, we are glad to help in any way. Sorry this continues. We look forward to the day when we can move on without these petty distractions.”

The Legal Battle

McRaney alleges in the lawsuit that NAMB and Ezell defamed him by demanding his firing from the Baptist Convention of Maryland-Delaware. McRaney says that NAMB threatened to withhold $1 million in funding if the state convention didn't comply. Additionally, the lawsuit alleges that Ezell discouraged other Baptist groups from hiring McRaney for consulting or speaking engagements. The dispute centers around whether civil courts should adjudicate a ministry dispute between cooperating Baptist organizations.

NAMB’s Position

In oral arguments heard by the U.S. 5th Circuit Court on April 4, NAMB attorney Matthew Martens emphasized that the dispute fundamentally involves ministry matters. McRaney, a Baptist minister, sought civil court intervention to address his work-related interactions with Baptist organizations. Martens cited 1 Corinthians 6:6, which questions taking disputes before unrighteous courts instead of resolving them within the faith community. He argued that civil courts lack jurisdiction in such cases.

Ezell’s email to state executives – published below – includes direct quotes from the appeals hearing to clarify NAMB's position.

Many SBC leaders believe NAMB’s argument to the court is highly problematic for Baptists. Their open letter published later in this article details what they believe are “fallacies and dangers” in NAMB’s argument.

Below is Ezell’s letter in its entirety:

Direct Quotes By NAMB’s Lead Counsel, Matthew Martens

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit — Oral Argument, April 4, 2024

“This dispute is fundamentally a ministry dispute. Will McRaney, a Christian minister and leader of a religious organization, is asking a civil court to adjudicate how two cooperating Baptist organizations interacted concerning his work as it related to those organizations’ joint ministry. That’s fundamentally the dispute here. And, respectfully, civil courts have no say in a dispute of that sort.”

Indeed, the point of 1 Corinthians 6:6 is that these issues should not be presented to a particular court but rather resolved among believers.

“As demonstrated through the factual record developed on remand, Baptists interact through voluntary cooperative relationships or associations, between autonomous entities rather than through hierarchies.”

“So, for example, hundreds of Baptist churches in Maryland partner together with each other to form BCMD. They do that voluntarily, while maintaining their autonomy. Likewise, NAMB partners with dozens of those state conventions. Again, they each maintain their autonomy and separate legal existence and yet they partner together in joint ministry.”

“In the Supreme Court’s decision in Watson v. Jones in 1871, the court made clear that ‘voluntary religious associations’, not merely churches, are entitled to freedom in their governance. And more recently, the Supreme Court affirmed that concept in both Hosanna Tabor and Our Lady of Guadalupe, where the court explained that religious autonomy extends not only to churches but also to religious organizations of all sorts. And what the Watson court makes clear is that if you, as an individual, choose to ‘unite’ with a ‘voluntary religious association’ you are deemed to have impliedly consented to that association’s governance...”

NAMB has never once argued that it can govern any state convention. NAMB has instead argued that NAMB and the state conventions each decide for themselves the terms on which they will cooperate with one another, and each retains its autonomy and the right to discontinue its cooperation with the other. That voluntary cooperation is memorialized in a written agreement.

No individual who works for either of the ministries (e.g. NAMB or a state convention) who are cooperating and communicating with one another can sue one of those ministries because he or she disagrees with the manner of cooperation and communication by either ministry.

In other words, it is an individual (not the state convention) who — in the words of the Watson case — unites with one of the ministries cooperating together and who is thus governed by the terms under which the two ministries have chosen to cooperate.

“That Watson decision is phrased as applying to voluntary religious associations of all sorts because the government cannot preference one religious organizational structure over another, particularly when that structure is of doctrinal significance and basis.”

“This [Strategic Partnership Agreement] document is governing the voluntary cooperative relationship between NAMB and BCMD. And that governance question, regardless of whether it is a faith question, the governance question is beyond the bounds of the court. And that’s why the ecclesiastical abstention doctrine, as this court articulated in McRaney I, had to ask does it raise governance questions, does it raise faith questions, does it raise doctrine questions. Any one of those would be sufficient to invoke the doctrine. We argue here that there are faith and doctrine questions under the Baptist Faith and Message, but even more fundamentally and easily, it’s a governance question — how these two interact is the definition of a governance question. And so the governance prong of the ecclesiastical abstention doctrine, we believe, requires application of that.”

—

Amicus Brief Open Letter

Interestingly, Ezell’s letter came shortly after an open letter from signers of an amicus brief submitted last fall to the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals in the McRaney v. NAMB case was sent to trustees of the NAMB and SBC Executive Committee board of trustees. Among the signers of the amicus brief are Morris Chapman, former SBC president and president of the SBC Executive Committee, Georgia pastor Mike Stone, a former chairman of the SBC Executive Committee; David L. Thompson, former NAMB trustee chairman; and entrepreneur Rod Martin, a leader in the Conservative Baptist Network and former member of the SBC Executive Committee. Additional signers are included at the end of this article. The amicus brief submitted by the SBC leaders was the only brief approved by the Court. An amicus brief submitted by the SBC Executive Committee was rejected by the Court.

Below is the open letter in its entirety:

An Open Letter to Trustees of the North American Mission Board, the SBC Executive Committee, and all who cooperate with the SBC

Baptists face issues that threaten our ability to advance the Great Commission. No issue endangers those who cooperate with the SBC more than the arguments advanced by the North American Mission Board (NAMB) in their ongoing lawsuit with former NOBTS professor and Maryland/Delaware Baptist Convention Executive Director, Dr. Will McRaney. Key concerns in NAMB’s argument include:

Partnership with NAMB brings outside organizations like churches, associations, conventions and ministers under NAMB’s governance and partners must submit to NAMB’s governance

NAMB claims the “right to interfere” with a partner to “protect its own economic and other interests”

NAMB claims that even if it defames an employee of a partnering organization that NAMB is protected from legal liability

NAMB’s argument undermines the religious liberty of partners and ministers

NAMB seeks legal exemption from otherwise illegal actions based on ministry partnerships

NAMB’s defense before the U. S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals echoes the ERLC amicus brief on behalf of NAMB that said Southern Baptist governance is a hierarchy, with the SBC at the top and all churches, associations, conventions and Baptist ministers falling under the governance of the SBC.

On April 4, 2024, NAMB Trustees and President, through their attorney, presented their argument before the U. S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. To hear the entirety of the oral arguments, click on the link at the end of this letter. The following two paragraphs of NAMB’s argument are most concerning (in the audio recording linked below, this begins at 20:19):

In the Supreme Court’s decision in Watson v Jones in 1871 the court made clear that “voluntary religious associations, not merely churches, are entitled to freedom in their governance.” … And what the Watson Court makes clear is that if you as an individual choose to “unite” with a “voluntary religious organization, or association”, you are deemed to have impliedly consented to that association's governance.

And I think the passage from Watson is critical. The court said the right to organize voluntary religious associations to assist in the expression and dissemination of any religious doctrine and for the ecclesiastical government of all the individual members, congregations and officers within the association is unquestioned. All who unite themselves to such a body do so with an implied consent to this government and are bound to submit to it.

Key to NAMB’s argument before the court is that any religious organization that partners with NAMB falls under NAMB’s “governance,” and, shockingly, they are “bound to submit” to NAMB’s governance. While NAMB was careful not to use the word “hierarchy” in its argument, by partnering with NAMB you must submit to their governance, which functionally establishes a hierarchical relationship between NAMB and its partners. Furthermore, if NAMB chooses to defame you or interfere with your employment for failure to submit to them, NAMB cannot be held legally liable for any damage they might inflict.

The oral argument by NAMB to the Fifth Circuit Court is consistent with NAMB’s written defenses and arguments before the U. S. District Court. Note these in particular:

“NAMB had the legal ‘right to interfere’ to protect its own economic and other interests.”

“NAMB is protected by an absolute privilege with regard to any statements it may have published regarding Plaintiff.”

“NAMB is protected by a qualified privilege with regard to any statements it may have published regarding Plaintiff.”

“NAMB is protected by an absolute privilege and/or a qualified privilege with respect to all decisions it made and/or actions it took which may have related to or had an effect upon Plaintiff’s employment with BCMD.”

NAMB claims it can say and do what it wants regarding churches, associations, conventions, ministers, etc. with whom it partners, because by partnering with NAMB they have implied consent to NAMB’s governance and must submit to NAMB’s governance. NAMB’s defense includes the right to defame, slander, libel, and interfere in ways that threaten the employment of individuals, without NAMB being subject to any legal accountability or potential liability. That is what NAMB is arguing to the precedent-setting second highest court in the United States. Moreover, McRaney’s legal complaint is that NAMB continued to defame him, and interfere with his employment opportunities, even after he was no longer employed by the BCMD.

In addition to the concern for individual Baptist bodies and leaders that NAMB’s legal defense introduces, there is also the danger of ascending and descending liability. If partnering with NAMB means you are under NAMB’s governance, does this also mean the partnering organizations are at risk should one of the partners be held legally liable in a lawsuit? If a partnering organization falls under NAMB’s governance, and someone in that partnering organization commits a criminal offense, can NAMB be held liable when lawsuits are filed against the partner? These are questions that NAMB Trustees should be asking.

Moreover, NAMB Trustees, and every Baptist and Baptist body, should be alarmed that an SBC entity is arguing in court that they have a right to defame and interfere with a person, simply because his Baptist organization partners with that SBC entity. NAMB is seeking legal exemption from otherwise illegal actions based on ministry partnerships. Though U. S. courts may or may not determine they have jurisdiction in this matter, is there no fear of God when we mistreat a brother? Does NAMB’s argument to the court build trust and goodwill with other partners? Is the threat of ascending and descending liability not of great concern to NAMB Trustees, and others, when NAMB claims partners fall under NAMB governance?

NAMB has taken a position that Baptist authorities and leaders all agree is contrary to the historic position and practice of cooperating Baptists. This has fractured cooperation and places at risk the cooperative efforts to reach the lost so dear to generations of Baptists.

Dr. Barry Hankins, Baptist scholar of Church-State relations, in his expert report to the courts, stated, “If NAMB’s interpretation of the First Amendment prevailed, every Baptist entity that cooperates in any way with the SBC would be put at risk.” Moreover, Dr. Hankins stated, “It is my opinion as a scholar of Church-State relations in the U. S. that NAMB’s First Amendment defense in this case, if accepted by courts, would actually undermine religious liberty rather than safeguard it.”

WHAT IS NAMB REALLY UP TO? If Southern Baptists are driven by a hunger for the lost and have an overwhelming desire to reverse the fourteen years of precipitous declines in evangelism, baptisms, cooperative program and church planting, we must act now. There is an existential threat in the SBC. While we have stood by, the autonomy of churches, Baptist bodies and ministers have been hijacked by the NAMB. We request that the NAMB Trustees abandon their dangerous anti-Baptist assertions and erroneous defenses made to the court and resolve this case. If NAMB Trustees fail to act, we ask the SBC Executive Committee to act in accordance with its duty because NAMB’s intentional misrepresentations to the courts have damaged the SBC and all cooperating Baptists.

—

Autonomy at the Core of Argument

At its core, this legal battle isn't just about McRaney or NAMB – it’s about the autonomy of Baptist churches. If NAMB's actions can influence state conventions to terminate leaders, what does it mean for local congregations? Southern Baptists must grapple with questions of authority, independence, and the delicate balance between denominational structures and local church governance.

Transparency and Accountability

McRaney’s quest for truth resonates with many. As evidence emerges and sworn testimony unfolds, Southern Baptists will witness the inner workings of their institutions. Transparency matters, especially in the church and denominational context. Whether you're a pastor, a layperson, or a concerned member, this case underscores the need for accountability within Baptist organizations.

Conclusion

In summary, the McRaney case highlights tensions within the Southern Baptist Convention, where ministry disputes intersect with legal proceedings. As the legal battle continues, both sides grapple with questions of authority, cooperation, and the role of civil courts in resolving internal conflicts.

--

Additional Amicus Brief Signees

Other signers of the amicus brief are Randy Adams, executive director of the Northwest Baptist Convention; Steve Ballew, executive director of the Baptist Convention of New Mexico; Bill Barker, pastor of Wolffork Baptist Church, Rabun Gap, Ga; Alex Barrett, pastor of Ridgeview Church, Fontana, Calif.; John Batts, pastor of Clear Creek Baptist Church, Silverdale, Wash., and a trustee of the SBC Executive Committee; Bryan Bernard, lead pastor of Redemption Church, Corvallis, Ore.; Jim Brunk, pastor of Cookson Baptist Church, Cookson, Okla.; Joel Breidenbaugh, pastor of Gospel Centered Church, Apopka, Fla.; Harold B. Bullock, former senior pastor of Hope Church in Fort Worth, Texas; Terry M. Buster Sr., pastor of First Baptist Church, Phil Campbell, Ala; Jared Byrns, pastor of Central Baptist Church in Lawton, Okla.; Travis Cardwell, lead pastor of University Park Baptist Church in Houston; Ken Cavey, pastor of Bethel Baptist Church in Ellicott City, Md.; Jason Cole, pastor of First Baptist Church in Simsboro, La.; Bruce M. Conley, director of missions for Blue Ridge Baptist Association in Boonsboro, Md.; Randy Covington, executive director of Alaska Baptist Resource Network; Rock Dearfield, pastor of Second Baptist Church in Ashland, Ky.; Steve Dennis, pastor of First Baptist Church in Checotah, Okla.; William G. Dowdy Jr., pastor of Magnolia Baptist Church in Laurel, Miss.; Bob Farmer, senior pastor of Grace Baptist Church in Rogue River, Ore.; C.W. Faulkner, pastor of First Baptist Church in Wolfforth, Texas; Joe Flegal, former director of evangelism and church health, Northwest Baptist Convention; Michael Freeman, lead pastor of Valley Christian Fellowship, Longview, Wash.; Russell Fuller, former professor of Old Testament, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary; Seth Gatchell, pastor of Pacific Church of Irvine, Calif.; Warren Gilpin, pastor of Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Norman Park, Ga.; Bobby Gilstrap, former state convention leader; Ron F. Hale, former member, SBC Executive Committee and former NAMB missionary; Adrian W. Hall, former evangelism director, Northwest Baptist Convention; Thomas Hardy, pastor of Peninsula Baptist Church, Portland, Ore.; Jeff Hessinger, senior pastor, First Baptist Church, Thompson Falls, Mt.; S. Grant Hignight, associational mission strategist, Mercer and Thomas County Baptist Associations, Thomasville, Ga.; James Bo Holland, pastor, Living Hope Baptist Church, Tulsa, Okla., and former church planting director for the Baptist General Convention of Oklahoma; Donna Jefferys, former executive assistant and office manager, Baptist Convention of Maryland and Delaware; Dale Jenkins, pastor, Airway Heights Baptist Church, Airway Heights, Wash., and former trustee of the SBC Executive Committee; Thad King, pastor, Pierpoint Church, Huntington Beach, Calif; Chris Kruger, pastor, Dayspring Baptist Church, Chehalis, Wash.; Randy Lanthripe, executive director, 17:6 Church Network and pastor, Church in the Valley, Ontario, Calif.; David Leavell, transitional revitalization pastor, Southwest Baptist Church, Bainbridge, Ga.; Daniel A. Lee, pastor, Bethel Baptist Church, Greenville, S.C.; Tom Melzoni, senior vice president, Horizons Stewardship and former senior executive pastor at First Baptist Church of Dallas; Gus Nelson, lawyer and ordained Baptist preacher; Dan Panter, pastor, McKenzie Road Baptist Church, Olympia, Wash.; Rick Patrick, pastor, First Baptist Church, Sylacauga, Ala.; Dennis Phelps, pastor, Coronado Baptist Church, Hot Springs Village, Ark.; Michael Poff, senior pastor, Cornerstone Baptist Church, Warrenton, Va.; David H. Rhoades, senior pastor, Broadview Baptist Church, Lubbock, Texas; Lewis Richerson, pastor, Woodlawn Baptist Church, Baton Rouge, La.; David B. Roberts, pastor, Emmanuel Baptist Church, Midland, Mich.; Robert D. Rodgers, retired vice president, SBC Executive Committee; William Schmautz, pastor, East Valley Baptist Church, Spokane Valley, Wash.; Clint E. Scott, senior pastor, Hilltop Baptist Church, Green River, Wy.; Jeffery Stading, pastor, Friendship Baptist Church, Hudson, N.C.; Keith Stell, senior pastor, New Georgia Baptist, Villa Rica, Ga.; Ben Trigsted, pastor, First Baptist Church, Castle Rock, Wash.; Bevan Unrau, senior pastor, Seabreeze Church, Huntington Beach, Calif,.; Steve Wolverton, pastor, Canton Baptist Church, Baltimore, Md.; Tim Yarbrough, former editor, Arkansas Baptist News.